Photos show rare glimpse into Black familyâs life before, after Birmingham bombing: âThis is his legacyâ

This story is part of AL.com’s “Season of Change: 1963″ series.

Hundreds of photographs fill the childhood home of Lisa McNair and her sister, Kimberly McNair Brock.

The pictures, shot by the late Chris McNair, show a part of Black life – and glimpses into the civil rights movement – through the lens of one of a few Black professional photographers documenting Birmingham in the 1960s, before and after the bombing at 16th Street Baptist Church that killed his daughter, Denise.

In one photo, Martin Luther King Jr.’s daughter Yolanda is peering into the camera while her father’s immersed in conversation. In another, taken at a dinner hosted by comedian Dick Gregory, Coretta Scott King is laughing so hard that she smudged her makeup. Another shows a men’s meeting, in an unknown location, strategizing for freedom.

“I love that this is his legacy,” said Lisa as she flipped through her father’s photo album at the family’s dining room table. “I don’t think he really knew what his legacy was, he thought it was something else. But this, us, and these images are his legacy.”

“They’re history,” Kimberly added.

Though McNair’s photos were published nationally, on the covers of Jet and Ebony magazine, many of his photos exist only in that album. Many have never been processed or digitized. Others, digitized but rarely seen, show Gov. George Wallace during his Stand in the Schoolhouse Door and Martin Luther King Jr. preaching in Birmingham. They are new angles on historic events.

Dr Martin Luther King speaks at a Civil Rights meeting at 16th Street Baptist Church in 1963 in Birmingham, Alabama. (Photo by Chris McNair/Getty Images)Getty Images

“Chris McNair’s photography started in a colloquial sense, where he would go to affairs in the Black community, to gathering places in the Black community and he would capture those things, and this is before the loss of his daughter,” said Barry McNealy, an archivist at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute.

Chris McNair’s oldest daughter, Denise, and three other girls – Addie Mae Collins, Carole Robertson and Cynthia Wesley – were murdered on Sept. 15, 1963, when Klansmen planted a bomb under the steps of 16th Street Baptist Church before a Sunday youth program.

After learning his daughter had been killed, Chris McNair returned to the church to snap a photograph of the wreckage – he carried his camera everywhere – before grief overwhelmed him.

A view of police activity outside the bomb damaged 16th Street Baptist Church on September 15, 1963 in Birmingham, Alabama. This is the only photo Chris McNair shot after the bombing of the Church. His only child, Denise McNair was killed in the bombing. (Photo by Chris McNair/Getty Images)Getty Images

McNair would become “fundamental in telling the story of the civil rights movement,” McNealy said. McNair later served on the Institute’s board of directors for several years.

“Since he was in the community, and people knew him, he could get access to events where other people might have been questioned,” he said. “Commissioner McNair was able to go into some doors where other people couldn’t go.”

Lisa, born a year later, and Kimberly, born five years later, never knew their sister. But through their father’s photographs, they’ve found a way to preserve her legacy, too.

“Being that we didn’t get to meet her, photographs are really the main way we get a chance to know who she is,” Lisa said in a recent interview with Reckon’s Black Joy and AL.com.

‘This is his legacy’

In Birmingham, many knew Chris McNair as a talented wedding and event photographer, who later became a state legislator and county commissioner. Others knew him as their neighborhood milkman growing up.

To Lisa, he was “Daddy” – a kind-hearted man who was always cracking jokes, doing silly dances and trying his best to keep the family together. Her mother, Maxine McNair, who died in 2022, was a very happy person, too, who “knew how to have peace,” she said.

“They found their joy in us and our antics and teaching us things, sharing things with us, sharing their experiences,” she said. “It’s not that you ever forget about Denise and the other girls, but you know, you live, and you have to go on living and hoping for a better day.”

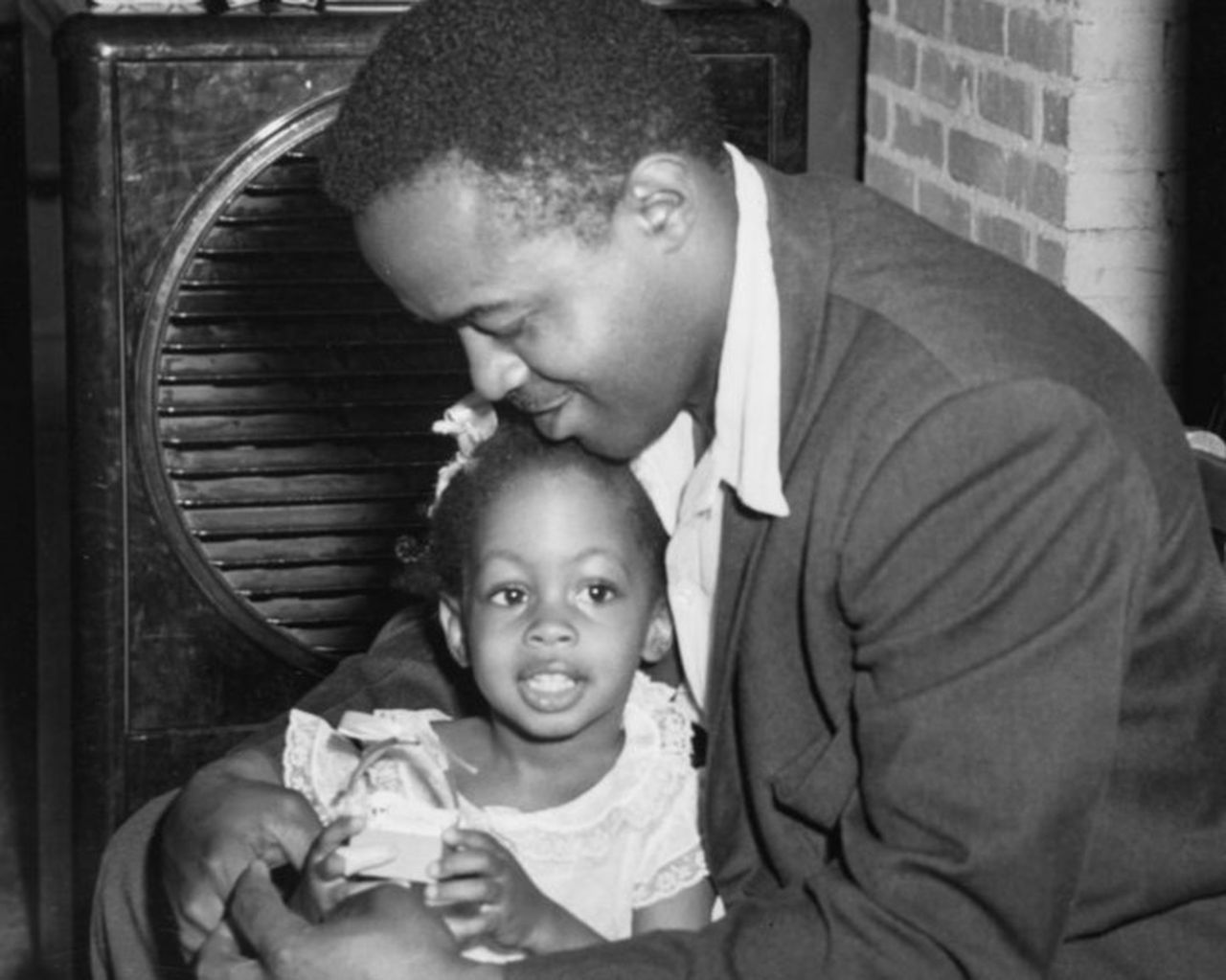

Chris McNair holds his daughter, Denise, in a self-portrait taken around 1954. Denise McNair died in the 1963 Birmingham church bombing. Credit Christ McNair. Getty Images.

He took Lisa and Kimberly under his wing, bringing the young girls along to wedding shoots and teaching them how to get the best shots.

Lisa, who now owns her own photography business, Posh Photography, says she still holds on to many of those lessons.

“You’ve got to get in there and be part of what’s happening so that you’ve got to get the best picture,” she recalled him saying.

Many of Chris McNair’s photographs give a sense that he was there in the room when change was happening. He captured close-up moments with icons such as King, Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, A.G. Gaston and prominent civil rights lawyers that were used by newspapers for decades.

As part of its yearlong commemoration of the civil rights movement of 1963, the City of Birmingham is now displaying a collection of Chris McNair’s photographs at city hall this month. The exhibit will run through Sept. 29.

“It was important to the City of Birmingham to honor the legacy of the late Chris McNair because he captured a very special part of our history,” said Marie Sutton, a spokeswoman for the city. “His photographs tell the story of how – 60 years ago – local preachers, community leaders, businessmen, and everyday people advocated for equal justice and we are all the beneficiaries.”

It wasn’t until the early 2000s, however, that the McNair sisters realized the depth of their father’s work.

In his basement, Lisa found collections of photos of King’s funeral that had never been printed. He’d kept countless photos from shoots of Black weddings and Black family portraits, before white clients started to ask for his services. Other boxes contained dozens of slides of the girls and his family that “were just fantastic,” she said.

“As it turned out, he captured a lot of Black life that wasn’t being captured by many other people,” she said.

‘The only way we’re going to heal’

Amid those collections are several of Denise. Snapshots of a happy toddler taking her first steps, blowing out the candles on her fourth birthday and playing with the dogs. An iconic black and white portrait, enhanced with a layer of paint and colored pencil.

A portrait of Denise McNair that her father, Chris McNair, shot and colorized with paint and pencils. By Chris McNair. Courtesy of McNair family.

“He was always talking about the cast lights, get the cast lights in her eyes,” said Lisa, pointing to the detailed specks of white lining her sister’s bright brown eyes.

A copy of that original portrait sits on the fireplace of the McNair family home. To the left is a photo of Denise and their cousin Lynn – The two “went everywhere together,” Lisa said.

The family pass on memories of Denise in other ways, too, Lisa said, recalling jokes about her sister’s love for “Mama Helen,” her mother’s cousin who lived a few houses down the street and always gave out snacks and extra food.

In her memoir “Letters to Denise,” published last year, Lisa writes to her older sister, explaining cable TV, the internet, private school and their parents’ grief.

“My life was much more integrated than her life was, and I wanted to share with the world what that was really like for me, being part of the first generation of African Americans to move freely in this country after segregation,” she said.

She also talks to Denise about the ways that she believes the world is reverting backward.

Last April she was snubbed from a chance to speak at a school in Florida, where Gov. Ron DeSantis banned lessons about so-called “critical race theory” in local schools. Many educators have criticized the legislation, fearing it limits discussions about race and racism in the classroom.

A few days later, Lisa took a framed black and white photo of her sister, wearing white pajamas and holding a blond baby doll, to Alabama’s capital, urging lawmakers not to erase Black history – and her family’s story.

She hopes the world won’t forget Denise. “The only way we’re going to heal,” she said, is to tell the truth and accept the truth.

“She didn’t give up her life,” Lisa said. “It was taken for hate, senseless hate and racism, just because of the color of her skin. And how she could have been so many things had she had the opportunity to live and be a full-fledged child and human being and American in this country, and things she could have brought to this world and this country. That was all taken away because she was killed for no reason.”